A hard Brexit could cost the UK’s automotive, technology, healthcare and consumer goods sectors a total of almost £17 billion per year in lost EU export revenues, according to ‘the realities of trade after Brexit’. The report, launched today by global law firm Baker McKenzie, covers four sectors that account for 42 per cent of the UK’s manufacturing GDP and 45 per cent of manufactured exports to the EU.

Produced in conjunction with leading economic consultancy Oxford Economics, the report forecasts the extent to which increases in costs to UK exports could lead to EU consumers switching to a domestically produced alternative or to a different exporting country, and the subsequent decline in UK export revenues.

The report also considers the best opportunities for the UK with third country markets outside the EU to offset the potential losses associated with departing the Single Market.

The impact of a hard Brexit is most notable in the consumer goods and automotive sectors, with a predicted £7.9 billion loss in annual UK to EU export revenue in the Automotive sector and a £5.2 billion loss in the Consumer Goods sector.

Commenting, Baker McKenzie trade partner Jenny Revis says, ‘These figures indicate the extent to which the UK’s key manufacturing sectors are likely to be hit by the impact of a hard Brexit. You can understand why there is now mounting pressure for the UK to negotiate new customs arrangements for post Brexit trade with the EU and for companies to work with their industry groups to help shape future trading relations with the EU.’

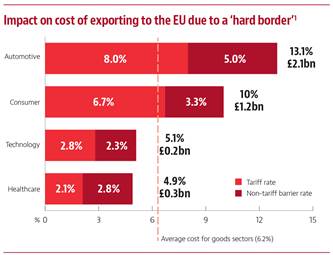

Tariff and non-tariff barriers to cost £3.8 billion annually

The report highlights that the automotive, consumer, technology and healthcare sectors could be hit with new tariff and non-tariff barrier rates as a result of the imposition of a hard border between the UK and the EU, predicted to total £3.8 billion annually. The cost of non-tariff barriers, which include new compliance paperwork and other administrative requirements, can match or even outstrip the tariffs themselves in some sectors, such as healthcare.

Of the four sectors, the automotive industry is likely to be hardest hit, with tariff and non-tariff barrier costs set to rise by an additional £2.1 billion annually, as the following chart illustrates:

‘The UK government has always been against barriers to trade, including non-tariff barriers. Some would say that the whole raison d’etre for Brexit is to remove obsessive standard-setting, categorisation and licensing of products from the UK but this certainly won’t be the case if we see a hard border between the EU and UK. Companies need to begin quantifying the non-tariff costs so there are no hidden surprises,’ says Baker McKenzie trade partner Ross Denton.

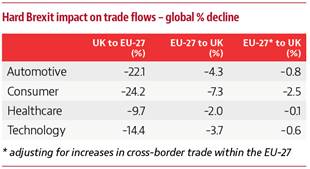

Proportionate fall in UK exports to be four times the decline in EU exports

Both the UK and the EU will feel the pinch on trade from the impact of a hard Brexit and from the additional costs from tariff and non-tariff barriers, however the impact will be significantly greater for the UK.

The report shows that for the four sectors, the EU accounts for 49 per cent of UK exports while the UK accounts for just nine per cent of exports from the EU. This demonstrates that the UK is highly dependant on the EU and, as a result, the proportionate decline in UK exports will be four times the decline in EU exports in these sectors – even before taking into account increased trade within the EU-27.

This dynamic exists in each of the sectors modelled. Indeed, in the automotive sector, without the UK as a trade partner, the report forecasts that EU exports globally could fall by 4.3 per cent, or just 0.8 per cent adjusting for increased cross-border trade within the zone. By contrast however, the UK automotive sector stands to lose more than 22 per cent of its export revenue as a result of reduced exports to the EU.

‘The combination of rising prices and softening margins could result in significant trade deficits,’ says Sunny Mann, Baker McKenzie trade partner.

‘We are working with many clients to consider if and where they can alter supply chains to reduce their reliance on the EU,’ he adds.

‘We have heard a lot about how much Europe exports to the UK, for example, in the automotive sector,’ says Ross Denton, Baker McKenzie trade partner.

‘That may be true in numerical terms, but when you look at this as a percentage of their trade, you can clearly see that the EU exports a lot more broadly, to a whole host of other markets, and consequently, it is far less dependant on the UK as a market than the UK is on it. This will have significant implications for upcoming negotiations.’

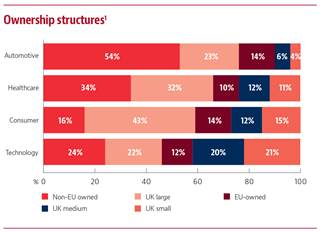

The risk of business relocation

In addition to the impact on export revenues, there is a significant risk that companies operating within the automotive, technology, healthcare and consumer goods sectors could relocate.

In many of the industries modelled by the report, there is a sizeable share of non-EU overseas ownership. These companies were likely motivated to base their operations in the UK because of the Single Market access it offered and could seek to relocate if that market access is revoked.

More than half of the automotive sector is owned by non-EU parent companies, while 44 per cent of the healthcare sector is comprised of non-UK owned businesses. This, coupled with the potential costs that businesses face in the form of tariff and non-tariff barriers which could total £3.8 billion annually across the automotive, healthcare, consumer and technology sectors, mean that relocation is a distinct possibility.

Commenting, Baker McKenzie trade partner Jenny Revis says, ‘Keeping companies in the UK may depend on the willingness of the UK Government to offer incentives to industry, especially where support is needed to offset any new tariffs. For the short term, at least, such incentives will need to be balanced with EU rules governing state aid.’

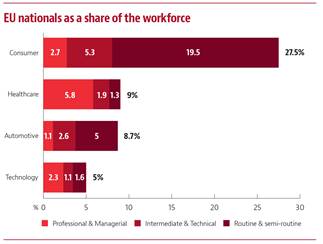

Consumer goods industry to face biggest squeeze in labour supply

According to the report, the projected impact of Brexit will not only lead to changes to capital flow but also to the labour supply which will be felt across each of the four UK manufacturing sectors. The consumer goods sector is the most vulnerable to potential Brexit-related skills shortages, because the EU provides more than a quarter of the sector’s total workforce. Those EU employees perform a wide range of roles across the industry, but the biggest proportion are in routine and semi-routine positions.

The automotive sector faces a similar challenge, albeit on a smaller scale, with almost nine per cent of its staff comprising EU nationals, the largest quotient of which are in routine roles. In the healthcare industry, concern lies not solely with the volume of staff that could be affected by tighter EU immigration controls, but with the proportion of skilled staff whose positions may be in doubt post-Brexit. Almost ten per cent of the sector’s workforce come from the EU and more than half of that group are in professional and managerial positions.

Indeed, in a study commissioned by Baker McKenzie earlier this year, skilled workers from EU-27 Member States said they felt more vulnerable to discrimination since the Brexit referendum, with 56 per cent of those polled indicating they could depart the EU before the end of the two-year negotiation period. In the healthcare sector, the rate was even higher with 84 per cent indicating a desire to leave. The challenges were similar in the technology sector, where 64 per cent of skilled EU workers planned to leave the UK.

Stephen Ratcliffe, Baker McKenzie employment partner, says ‘Such rates of departure could leave the industry with a significant skills gap to plug post-Brexit. Companies need to look now at how they can support EU staff facing uncertainty over the right to remain in the UK, particularly in light of recent suggestions around the future restrictions on the rights of EU citizens seeking to live and work in the UK.’

Ratcliffe adds, ‘The government can’t have a permanent situation in which it’s easy to come to the UK to do routine work. There’s no simple solution, but there is an urgent need for clarity over the types of highly skilled roles for which longer-term work permits may be obtainable.’

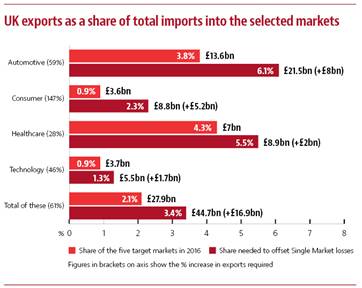

UK manufacturing exports to five key markets need to increase by 60 per cent to offset ‘hard Brexit’ EU export losses

“The realities of trade after Brexit” report also examines the third country trade opportunities in each sector post-Brexit based on the size of global imports to those markets – now and in the decade ahead. It reveals that, for every sector, the US offers the greatest opportunity, accounting for around half of the entire market in each of the industry sectors. China meanwhile, presents the second largest opportunity, with a fair amount of variation between the remaining sectors.

In these countries and sectors, the UK’s market share of imports was 2.1 per cent in 2016. It could need to increase over 60 per cent to offset Brexit-related export losses. Consumer goods in particular, could need to work harder than the other sectors to compensate for the loss in EU trade, with exports to these third country markets needing to rise by as much as 150 per cent.

However, domestic markets could also be an important factor in cushioning the impact of falling exports – particularly in the consumer goods sector, which has a large domestic customer base.

‘The UK is caught between a rock and a hard place on Brexit. Our data shows that the UK needs to begin the very lengthy process of negotiating Free Trade Agreements with third country markets now in order to mitigate the cliff-edge effect of the fall in trade in case no EU agreement kicks in immediately. But we can’t do this while we’re in the EU and have the safety net of an EU transitional period. This is a real quandary and the UK government will need to make some difficult decisions,’ concludes Samantha Mobley, London head of EU, competition and trade.